The secret to happiness? Stop trying to be happy.

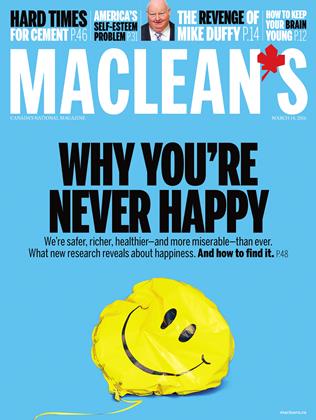

We’re safer, richer, healthier—and more miserable—than ever before. What new research reveals about happiness. And how to find it.

Cathy Gulli

March 5, 2016

A few minutes after Neil Pasricha learned his wife Leslie was expecting their first child, he got an idea for a book. They were sitting on a plane returning to Canada from a trip to Asia when a flight attendant handed them a plastic-wrapped muffin with a scrap of paper that read, “Congratulations!” Leslie had been sick toward the end of their vacation, and on a hunch she had picked up a pregnancy test during a layover—and taken it mid-flight. Pasricha’s first thought upon hearing the news: Tell someone! Hence the muffin.

His second thought would require more time and effort to materialize. Pasricha decided to write down everything he knew and was learning about how to be happy: “I couldn’t think of anything I wanted more for my child.” Almost two years later, Pasricha has finished a 275-page book called The Happiness Equation: Want Nothing + Do Anything = Have Everything. Whatever edits the copy has been through, the dedication has remained the same: “To my baby, I wanted you to have this in case I didn’t get a chance to tell you, love Dad.”

Just about every parent can relate to Pasricha’s wish for his child. His mother and father no doubt wanted the same for him. But Pasricha’s struggle to articulate what happiness is and how to achieve it has a particular resonance. This is, after all, coming from the guy who during the past decade, while working as a corporate leadership executive at Wal-Mart, started a blog, 1000AwesomeThings.com, which turned into the bestselling The Book of Awesome, an ode to everyday pleasures, which was spun off into three more Awesome books (plus a journal and five calendars), a popular TED talk and hundreds of other speaking engagements around the world.

Stratospheric professional success aside, Pasricha, 36, has much to be happy about: he owns a home in Toronto, has a loving wife, a young son and now a second baby on the way. Despite all of these accomplishments, and even the wisdom Pasricha imparts in his books, finding happiness has turned out to be as much a maze as a marathon for him. “I don’t feel like I’ve achieved any next-level enlightenment or nirvana,” he says. “I have intense daily, weekly and monthly net struggles.” Especially around how to juggle work and family time. “Dropping my son off [at daycare] and picking him up is really important to me,” says Pasricha, as an example of one thing that’s come under threat. “Seventy-hour weeks in an office [mean] no more breakfasts with my son.” So he recently did what many people who are similarly stretched often fantasize about. Pasricha quit his job at Wal-Mart with one plan in mind: “I’m actually right now in the throes of dedicating myself more fully to happiness.”

In this way, Pasricha perfectly represents an emerging generation of individuals across North America, and probably beyond, who are living a good life but wondering—or, more likely, worrying—about how it could and should be better, while trying valiantly to make it so. Often, they are at least adequately functioning by almost every external measure—employed, maintaining relationships and engaged with the world around them. But inside, they are still unnervingly dissatisfied. “Their problem is the goals they are pursuing don’t yield happiness,” says Tayyab Rashid, a psychologist and researcher at the University of Toronto. “[They] score a goal, and rather than enjoy it, [they] change the goalposts.”

Psychologists and sociologists call these people modern-day “seekers.” Historically, they may have been a bohemian minority, but today this sense of searching is altogether mainstream. It is less an artistic or intellectual pursuit and more an everyday one—a reflection of the anxiety so many people feel about how they live, and a confusion about how to be happy and what to prioritize: Work hard to get ahead but not too hard; be an involved parent but maintain your own interests. Whereas the dissatisfaction seekers felt 40 years ago may have been more with the world, now it’s with ourselves. Fretting and fighting feelings of inadequacy are the cultural equivalents of bell-bottoms and protest anthems. The self-help book industry proves it: A search on Amazon.ca for “happiness” turns up more than 49,000 results. A massive poster hung from the rafters of a bookstore greets shoppers, proclaiming, “The science of happiness: Crack the code to your happiest self.” Pasricha’s Book of Awesome sits on a table below it, alongside other cult classics. It’s likely The Happiness Equation will join them soon.

In theory, the pursuit of happiness is commendable; in reality, it may be making matters worse. “People give lip service to the idea that nobody’s perfect, but there are far too many people who want to be the one,” says Gordon Flett, the Canada Research Chair in personality and health and a professor at York University. “They’re searching for the trigger that will make them transform.”

Pasricha sees the irony: he embodies an answer to contemporary yearning even while his new book may fuel it. But he wrote it as much for himself as for his children or the general population. “I’m not offering New Age wisdom here. I’m offering age-old wisdom,” says Pasricha. “What I hope people feel when they read this is not, Ah-ha, that’s the trick! but, Oh yeah, that’s what I used to do or that’s actually how I feel!”

Indeed, if people recognize in Pasricha’s “values” some of their own but they can’t seem to live them out, that’s because they’re facing another, deeper dilemma: They are growing up or growing old in an era unlike any other in human history, where the basic instinct to survive has morphed into a complex desire to thrive.

More than 70 years ago, American psychologist Abraham Maslow came up with a theory of human motivation represented by a pyramid. Since then, as food, shelter, safety and security have become more easily attainable for the public at large, more and more people have climbed up Maslow’s hierarchy of needs—looking for love and belonging, self-esteem and respect, and, finally, self-actualization. They want to reach their full potential.

It’s no wonder then that so many individuals feel they’re constantly coming up short. Every day, people are attempting to summit the highest peak of human existence with almost no training, tools or sherpas to make it happen. “Self-actualization is equated with happiness and fully functioning, but very few people ever experience it, and even those who do attain absolute self-actualization often don’t [remain] at that level,” says Flett. “They have peak experiences or periods of optimal functioning but they’re not necessarily going to stay that way as they age or as life changes for them.”

What’s more, people today are caught in an evolutionary battle that belies the sophistication of contemporary civilization. The brain is hard-wired to anticipate and detect negative things as a matter of survival. But thriving requires seeing the upside of everything all the time. And that really is proving to be an uphill struggle. “Left to their own devices, our minds tend to hijack each and every opportunity for happiness,” says Robert Emmons, a pioneer of gratitude research and a psychologist and professor at the University of California at Davis. “Negativity, entitlement, resentfulness, forgetfulness and ungratefulness all clamour for our attention.”

Put another way, there is a fundamental disconnect between the way people live and what they want—between the way the brain works and what the heart longs for. Today, the public at large has more money, education, health, information, mobility, technology and rights and freedoms than ever. But, as Pasricha points out in his new book, studies show that individuals don’t report being any happier now than they did 50 years ago. So what is it going to take? “We all want to do, do, do, and achieve, achieve. Our culture is trending toward this whir, whir, you can hear the engine firing up,” says Pasricha. “It’s like you can’t stop getting better.”

Except that the better that individuals and society as a whole get, the more they expect of themselves and each other—and the more social arrangements require of them. Nowhere is that more evident than in the workplace. “Along with [any] status boost comes an avalanche of stress exposures,” says Scott Schieman, the Canada Research Chair in the social contexts of health and a professor at the University of Toronto. “That’s where you see more work pressure, more overwork, more work-family conflict.” He’s established a theory around this phenomenon called “the stress of higher status,” which maps out the paradox that as people move up the socio-economic ladder, they also slide down into “health-harming circumstances.” At a certain point, says Schieman, “there’s this diminishing return.”

That’s the ugly side of “extrinsic goals” such as “power, status, image, popularity and money,” says Veronika Huta, a psychologist and professor at the University of Ottawa, who studies the pursuit of pleasure (hedonia) versus personal growth and excellence (eudaimonia). “Extrinsic goals are either bad for you or they have no effect on well-being,” she says. But they’ve become an obsession nonetheless. Pasricha recently googled “how to be” to see what the search would turn up: the most commonly entered phrase was “how to be happy”—followed by how to be “rich” and “pretty.”

It’s hard to know what Google would have turned up 50 years ago had it existed—assuming people then would have even considered using a search engine for guidance on attaining personal goals. But today, the Internet is a primary resource in society the same way that religion may have been in the past. In an ever more secular, consumerist society, extrinsic motivators are a lot easier to come by than inward-looking ones. “What I see again and again is people looking to capture happiness and maybe self-acceptance, but they look to the external world,” says Paul Hewitt, a psychologist and professor at the University of British Columbia. What’s more, individuals often feel they are owed more happiness than they feel. “There’s a notion that you can expect to be happy. There’s a sense of entitlement that goes along with that, too: I’m supposed to be happy. If the world were fair, I would be happy. I should be happy.”

It’s a narcissistic approach that completely aligns with contemporary culture. When it comes to the drudgery of daily life—chores, grocery shopping, walking the dog, paying the bills—many people outsource and automate as much as possible. At work, as people advance they become specialists, or attempt to set themselves apart by excelling in a given area—they want to be the go-to person, to be known for something. Hobbies have become passions, but with an obsessive twist that can, at times, subvert the joy they are supposed to elicit: few people run without training for a race in mind, and home cooks often fancy themselves fledgling chefs while almost burning the house down.

Meanwhile, the best bits of daily life get documented and upsold on social media—preferably with photographic evidence of productivity and “happiness.” People are, in effect, looking outside of themselves for confirmation that life has meaning, in the same way people may look to work for purpose. They also want a community to rally around them. But the constant comparison allowed by social media exacerbates a tendency toward perfectionism that is surging in modern society.

“We’re often looking forward to what we don’t have and feeling that discontent. Goals are like that. The discrepancy between where we want to be and where we are does cause negative feelings,” says Fuschia Sirois, a former Canada Research Chair in health and well-being and a professor of psychology at the University of Sheffield in England.

That state can be motivating, Sirois says, but only to a point. Her research on the importance of “the journey focus” shows that people are better off when they simultaneously consider the past, present and future of their lives rather than than fixating on one period. “If we’re so focused on looking ahead, [when] we get to obstacles we can [feel] frustrated and forget about how far we’ve come,” she says.

In other words, the pursuit of happiness can take life’s complexity out of context. When people feel closer to happy, life is pretty good; when they are sad or stressed, life kind of sucks. Seeing day-to-day living in those extremes sounds ridiculous when articulated this way, but that’s exactly how many people experience it.

In The Happiness Equation, Pasricha talks about how everybody, no matter who they are, has 168 hours a week to use. That time usually gets divided into three buckets: sleep, work and everything else. It’s how people divvy up those hours between the three “buckets” that shows what they value—in theory and in practice. For Pasricha, too much was going into the work bucket, and that’s probably true for many others. But even time away from work can come with little aggravations. “I dropped a glass this morning; it shattered. My son was there. He didn’t want to get his coat on and we struggled,” says Pasricha. “I’m the same as everyone—still scrambling.”

Nonetheless, this is what he’s chosen for himself. Another person might load their buckets differently. There’s no wrong answer, says Pasricha; the main point is to be deliberate about what—or who—gets the most time and attention. In fact, despite all the complaining people do about their jobs, Pasricha says work does not, in and of itself, undermine happiness. Just the opposite. It gives people a purpose, in the grand sense of contributing to the world, and in a more personal but no less significant way—a reason to get out of bed, a means to feed the family.

Where work can sabotage happiness is when the amount of time individuals put into their jobs doesn’t translate into a good hourly wage. When people think in terms of annual income, they overlook their value on a daily basis in the workplace. In his book, Pasricha tells the story of a teacher, a retail assistant manager and a Harvard M.B.A. who all make the same hourly wage: $28—even though their annual incomes are $45,000, $70,000 and $120,000, respectively. (See chart for details.) “I have friends who work around the clock as downtown lawyers and they joke, ‘When I do the math, I actually make less than minimum wage,’ ” Pasricha writes. The message is obvious, then: overvalue yourself. “When you overvalue your time, you make more money by working fewer hours and earning more dollars per hour.”

The Happiness Equation is rife with provocative insights like this one, supported by formulas, tables and diagrams. In total, Pasricha outlines “nine secrets to happiness”; he advises people to do whatever they’re afraid of doing and to partner up with someone at least as happy as themselves. There’s even a calculation to figure out how much time a couple spends being happy together based on their individual dispositions and how one’s temperament influences the other.

In the end, much about the way people tend to pursue happiness today seems to actually work against achieving it. For Pasricha, there is only one thing to do: “Relieve yourself of all the external pressures, obligations and measurements you’ve internalized that are just totally strangling you every day. You got it good. You’re fine. Relax. You want happiness? Get rid of happiness.”

It’s a clever quip, but one that reflects a shift in the way happiness researchers are thinking. “I actually think that happiness is not quite the right word for what we’re all after,” says Huta. “Researchers are increasingly using the term ‘[the] good life’ instead, [which] does not imply a narrow focus on feeling well, but rather a comprehensive concept that includes feeling well, doing well and living well, so making meaningful and worthwhile choices.” It’s a fascinating shift.

There’s something to be said about the fact that when one person asks another, “How are you?” the response is almost always, “Good,” even if it’s not true; almost never does anyone respond with, “Happy.” A cynical interpretation would be that this question is just a meaningless exchange of niceties, a polite salutation more than a genuine query. But there’s another idea to consider: maybe in a subconscious way, most people know that overall they have it pretty good, that they shouldn’t complain, because whatever problems they’re having, the other person has some too. And even if things are going well, replying “happy” would just be weird. In a way, the answer to a simple question may be what so many people are searching for: Good is good enough. CG