Life with help: how did we get so useless?

We’ve outsourced our lives. Now we can’t do a thing for ourselves.

Cathy Gulli

May 15, 2012

There is no limit to what some people will pay for someone else’s time and sweat. Sheri Bruneau first learned that lesson four years ago when she quit teaching elementary students to start her own business, Get It Together, in Calgary. As a “personal concierge,” Bruneau takes on almost any task that needs doing for individuals who can’t or won’t do it themselves.

Last summer, for instance, “this gentleman phoned me and said, ‘What’s it going to cost to get you to go stand in line?’ ” Prince William and his new bride Kate were coming to town for the Stampede, and the man’s wife was desperate to see the royal couple. Getting tickets would require camping out on the street near the box office. “They were $30, I think. They were not extravagant,” she recalls. But the service fee was a different matter seeing as she arrived at 4 p.m. the day before the sale began and the line started moving 18 hours later. “I charged him another $200 because it was an overnighter.”

For Bruneau, it was all in a day’s work. And compared to other calls she’s taken, it was hardly any work at all. She’s packed, moved and unpacked entire houses for people. She’s delivered drug prescriptions, chauffeured women to weekly hair appointments, dropped off and picked up dry cleaning, organized cupboards and closets, and even renamed and re-filed computer documents for clients whose desktops had become cluttered.

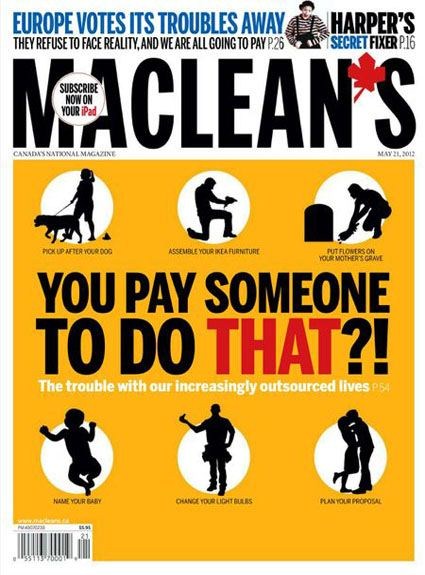

In other words, there is no job too trivial to warrant not enlisting a professional to do it. The hired help has moved out of the mansion and into more modest homes, too. Across the country, an army of entrepreneurial “experts” have emerged, charging as much or as little as their local market will allow, and promoting their services with old-school flyers, slick websites and persuasive online ads. They are ready and willing to do those tasks we used to do ourselves or with the assistance of a neighbour—be it scooping up dog poop in the backyard or assembling Ikea furniture or changing light bulbs or programming the remote control.

If nothing is too minute to contract out, then no job is too important or personal either. In her new book, The Outsourced Self: Intimate Life in Market Times, famed American sociologist Arlie Russell Hochschild explores the implications of hiring strangers to carry out what has historically been considered sacred labour done solo or with the support of loved ones: finding a mate, planning a wedding, scattering ashes, assembling a photo album, having a baby, naming a baby, raising children, visiting elderly parents.

“You can pay for anything now,” says Linda Duxbury, a professor of business and organizational health at Carleton University in Ottawa. “And if people can afford it, they’re doing it.” It’s ironic: as North Americans, we pride ourselves on working tirelessly; the average combined workweek for spouses in dual-earner couples was 77 hours in 2008, according to Statistics Canada. And yet, when you consider all the services we employ others to perform, you can’t help but wonder: how did we get so useless? And does it matter? What is lost, besides self-reliance, when we outsource so much of our lives?

“We’re in a new era,” says Hochschild, who is professor emeritus of sociology at the University of California, Berkeley. “We’re moving into an everything-for-sale society,” in which we increasingly apply a commercial mindset to personal life. “There’s a growth in the market way of thinking. The market itself is a bigger deal than it used to be. We have had services in the past, but not to this degree,” says Hochschild. “There didn’t use to be proposal planners or ‘Rent-a-friend.’ This has all flipped over on us so fast, within a generation.”

The dramatic change has been fuelled, in part, by the rise of two-income households with children over the last three decades. More work outside the home has made any work inside the home that much tougher to pull off. While experts suspect that outsourcing is mostly a middle- to upper-class phenomenon, families in every income bracket are invariably seeking the same thing: help. “All of these services actually feed on the idea that they will help you balance family and work,” explains Catherine Krull, a sociology professor at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. Or as Duxbury puts it: outsourcing “is always done in the name of finding more time.”

Whether it does, in fact, is debatable. Duxbury’s research indicates that whatever time people gain by getting, say, a housekeeper, they often spend at the office rather than with relatives and friends. Hochschild likens the promise of outsourcing to that which accompanied the dawn of kitchen appliances in the 1950s: “ ‘Oh, you have a new dishwasher, great! Oh, you have a new clothes washer, great! The new era of leisure has arrived for the homemaker,’ ” she recalls. But “it didn’t really.”

Still, it’s the best possible fix that many people can find today: “We live very high-stressed lives,” says Krull. “If someone offers to alleviate that, even a little bit, and you can afford that, aren’t you going to grab it?”

The answer is as unsettling as it is soothing: “Money can’t buy you happiness,” says Duxbury, “but it sure helps you cope with stress.” Even if all we may be buying is the illusion of accomplishment and freedom.

To hear Bruneau tell it, organizing shelves is, actually, the type of task that requires a professional’s guidance. Without it, “what happens is people will go to the store, and they’ll say, ‘Oh, this organizing tool looks great.’ Then they take it home, and they wonder, ‘Why isn’t it working?’ ” she says. Bruneau’s explanation? “It doesn’t fit with how they think.”

So when clients call for such help, Bruneau’s first step is to figure out if they are left- or right-brain dominant. “Right brain is more artsy, creative, and it’s all visual—so colour-coding works, and having things out [to see]. Left brain is more about structure and sequential order,” she says. For a woman who is right-brain dominant, Bruneau took the door off her cupboard, and “beautifully organized it with decorative supplies so it didn’t look gross, and so she couldn’t forget about it.”

What Bruneau knows about organizing is matched by her ability to read our collective desire to excel in all areas of life. “There’s this sense that we aren’t doing enough, that there’s all this other stuff that we could be purchasing or learning that will make us better,” says Krull, who is also an associate dean at Queen’s. “It’s a brilliant marketing strategy. It plays on that feeling of inadequacy.” Hochschild takes it one step further: “We’re a self-improvement-oriented culture. But it’s gone from self-help to other-help.”

Scanning the names of companies listed in the online Canadian Concierge Directory provides proof of how outsourcing is widely framed as the key to a more successful and less stressful life. Phoning up Time to Spare, Key to Health, Balance In Style, Urban Rush or Exceed could release you from the burden of returning merchandise, paying bills, mailing letters, picking paint colours, cooking, decorating your house, taking the pet to the vet, and even finding a good doctor or school. “When people call, they’re desperate, they’re overwhelmed,” says Mary Ann Westendorf, who established Bizzy Butler six years ago in Maple Ridge, B.C., outside Vancouver. “They trust the person they’re calling to help them.”

Adding to the allure of outsourcing is our growing fixation with specialization. While we pursue our career paths with zeal, other people are refining the art and science of baby-proofing a home or choosing the right clothes or teaching dogs not to bark. The thinking goes that it’s wisest to let the pros do what they do best—lest we mess up. “If you’re buying a car you want to do it efficiently, you want a pleasant experience, and you want the best price. That logic is creeping into our personal life,” says Hochschild. In her book, she tells the story of a father who insists on planning his child’s birthday party. “It backfired,” recalls Hochschild. “He tried to be a clown and nobody laughed. And a neighbour says, ‘Leave it to the experts. They know what five-year-olds think is funny.’ ”

As a parent, you might never believe a stranger—professional clown or not—could entertain your child better than you. Until, that is, you hire one. You might never think to employ someone to rearrange your furniture or declutter your garage, but after watching a few hours of HGTV you could be convinced doing so will significantly increase your property’s resale value. You might never think to hire someone to “teach you how to become so attractive to the opposite sex” or “plan a seven-day healthy menu” or “make a tough decision for you.” But when you see these ads on websites such as fiverr.com, where you pay $5 for any job listed, you might think, why not? (Although cost isn’t always an issue; Westendorf, for example, charges $50 an hour for home organizing.)

In this way, outsourcing also taps into consumer culture. “The service in and of itself becomes a commodity,” says Krull. “This is Canada’s new luxury item instead of a fur coat.” And for those families who have the financial means to outsource, the potential benefits are plenty. “Cleaning, chores, yardwork, shovelling—if these are a source of stress for you and you can get rid of them by paying somebody else, and you can afford to do that, then that actually is associated with a lot better mental health,” says Duxbury.

Some say outsourcing could even save a marriage: “Many people are working 50 hours a week, and their partner is working 50 hours a week. When you’ve got that and you’re squabbling about who is going to do this and who is going to that, it’s much better for the couple to spend the money on help than put stress on the relationship by arguing over things that really don’t or shouldn’t matter that much,” continues Duxbury. “When people say it seems stupid to pay someone, I always say, ‘It’s cheaper than a divorce.’ ”

Tarra Stubbins, president of Take It Easy personal concierge in Toronto, sees a growing inclination to devote any hours we have away from work toward doing what we enjoy most. “People are valuing their time more now. So they’re more willing to hire a cleaning company. That is extending to other services: ‘I don’t have time to take my car to get serviced. What’s more valuable to me, that or spending time with my children?’ ” Consumers, she says, are seeking a higher quality of life. Adds Westendorf, who counts among her clients many working professionals aged 40 to 65, “I have a lot of families who just want to take some of this stuff off their plate and hand it to someone else.” That echoes Bruneau’s experience: “They don’t want to spend time doing trivial things.”

At the heart of the outsourcing phenomenon is a frantic effort to buy time away from work and relieve anxiety and shame over how many hours we clock. Duxbury has seen this before, especially with regards to the way we eat. “We’ll spend a little more on specialty macaroni and cheese as opposed to Kraft Dinner because then we won’t feel so horrible that we’re not cooking ourselves,” she explains. “We’re a guilt-driven society nowadays. And we’re using money and paying for services to get rid of our guilt. Because it’s easier to do that than to say no to your boss or your kid.”

In many ways, outsourcing is self-perpetuating: the more we do it, the more we wonder how we could have ever done without it—how we could have managed to wash the windows, bring our junk to the dump, do all that ironing, and design a workout routine. Even Krull, who uses hired help at times, admits, “My life would be impossible without it.” The effect can often extend beyond a single household to an entire community: “Outsourcing adds to your status, your success, your ability to do it all, which raises the bar even higher and puts even more stress” on you to keep it up, she explains, and “on others who can’t afford it and feel they have to do it all themselves.”

Whereas we might have once relied on relatives, friends and neighbours to watch our kids or help us around the house or host a celebration, today those people are just as busy with their own lives. As a consequence, we have lost the “village” mentality that once sustained whole societies, and we have instead opened up a marketplace, says Hochschild. This new reality explains how even the most personal of acts such as putting flowers on graves of loved ones can be contracted out. “We’re living in an out-of-balance society.”

The battle for balance, however, is one we’ll never win on our own, experts agree. It is a bigger fight than any one family can ever hope to resolve alone. For Hochschild, whose previous books are about our perpetual search for balance—spouses attempting to share domestic duties, or governments and employers needing to offer family-friendly policies—the explosion of outsourcing suggests that as a society we are finally admitting defeat. “I worry that we’re leaving those challenges and social transformations behind. We might be saying, ‘Oh well, we’ll just have to buy ourselves out of this one.’ ”

To be sure, in many ways outsourcing reflects just how deeply we are buried. No matter how much we try to dig ourselves out, there is always more dirty work to be done. Few of us feel totally comfortable with contracting out tasks that we know we could, actually, do on our own under the right circumstances. “One sweet example,” says Hochschild, “is the woman who lied about making the lamb roast dinner herself.” Short on time or unable to cook, she was uneasy admitting it. “I think a lot of people feel that.”

Hochschild says that outsourcing occurs on a continuum—that hiring a personal organizer is different from hiring a clown to entertain your child. “A closet is a closet, so big deal. You didn’t care about it before you called someone to fix it, and you don’t really care that much after,” she says. But when we can’t make our kids laugh, that is unsettling. “It suggests an emotional detachment from knowing your child’s tickle bone, a detachment from a personal web of relationships.”

Outsourcing might not be an ideal answer, but many people would say it’s better than the alternative, which is to do nothing except continue to run ourselves ragged. So while we hire retirement home consultants and dog walkers, we might contemplate the future and how it could be better. Duxbury has given it some thought, and she suspects that her own daughter will have learned more than a thing or two about the pursuit of balance from watching her mother all these years. Chances are, Duxbury predicts, the next generation will actually pay for help more often than their parents—but not because of gruelling jobs and domestic duties. Rather, they will work less inside and outside the home in lieu of other, more fulfilling, ways to live life.

“Our children have seen us hiring out, struggling, spending huge hours at work for an organization that doesn’t appreciate us. They’ve seen us get divorced and on prescription drugs. They’ve seen us take stress leave,” says Duxbury. In the time ahead, “we’re going to see them saying no a lot more often, and paying for a lot more leisure. They will say, ‘Perfection comes at a cost, and so I’m willing to lower my standards.’ They’ll say, ‘Screw it all.’ ”

In effect, they will do for themselves what their parents couldn’t or wouldn’t. CG